Continuing Glosso’s telling of the OED birth story…

Five years into the New Dictionary project, in 1884, James Murray and his family moved to a large house in north Oxford, where he built a second – larger – Scriptorium in his back garden, to store the growing mountain of paper slips that were flooding in for him and his team following his Appeal (see yesterday’s Glosso post). The Scriptorium, crafted from corrugated iron, was lined with wooden planks, book shelves and 1,029 pigeon-holes for the quotation slips. Anything addressed to ‘Mr Murray, Oxford’ would find its way to him, and the volume of mail sent by Murray and his team was so vast that the Post Office erected a special mailbox (or what the British call “postbox”) outside his house, which he had named ‘Sunnyside’. Among those slips of paper were some penned by a notorious murderer detained at the even more notorious Broadmoor.

Enter Dr. William Chester Minor

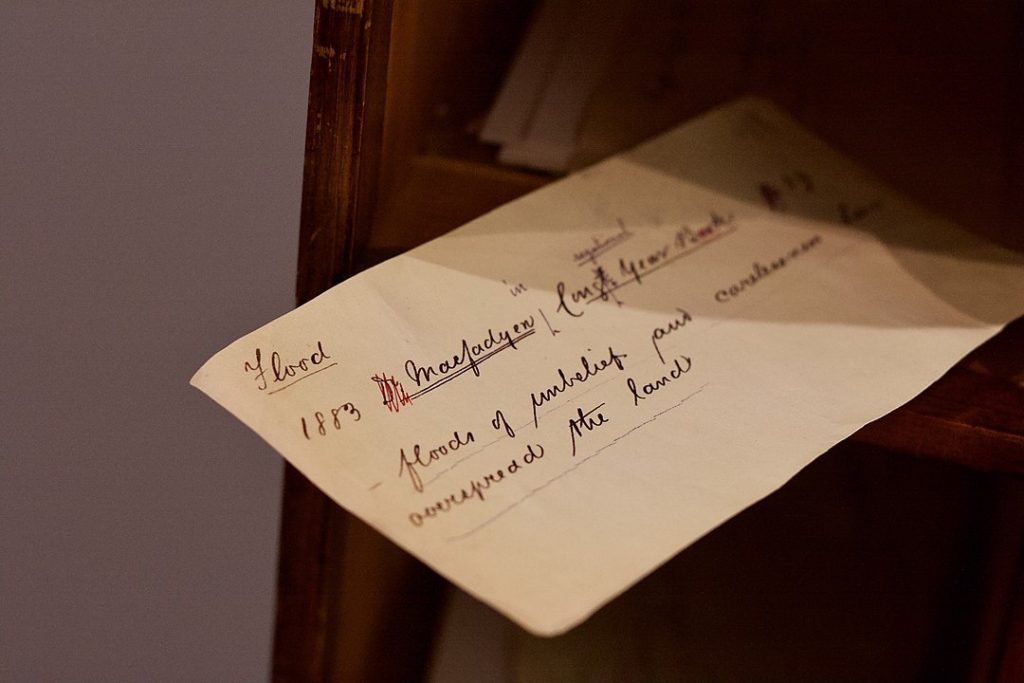

William Chester Minor was born in Ceylon to Congregational church missionaries from New England in 1834, just three years before the birth of the Scottish lexicographer who would come to determine William’s ultimate mission in life. At 14, William was sent to the United States, where he lived with relatives in New Haven while attending Russell Military Academy. He eventually enrolled at Yale Medical School, supporting himself during his medical student years with part-time employment as an instructor at the Russell Academy and as an assistant on the 1864 revision of Webster’s Dictionary, which was then in preparation at Yale. Like Murray, Minor was a man of words. After graduating from Yale with a medical degree, he joined the Union Army. The story goes that Minor, who served as an army surgeon during the American Civil War, was made to punish an Irish soldier by branding him on the face with a D for “deserter” – and that this incident (which has been largely dismissed as fabricated) was said to play a role in Minor’s subsequent mental deterioration. At the end of the war Minor was dispatched to serve in New York, where by night he had a predilection for consorting with prostitutes. By 1868, his mental condition had worsened to the point that he was admitted to St. Elizabeths Hospital, then called a ‘lunatic asylum’, in Washington DC. Within a year or two, not having shown any improvement, Minor left for London to seek a change to improve his mental state. It was there, still beset by paranoid delusions, that he fatally shot a man whom he wrongly believed to have broken into his room. Found not guilty of the crime by reason of insanity, Minor was duly incarcerated at Britain’s notorious Broadmoor Asylum for the Criminally Insane, where he was detained for the next nearly 40 years. Since the fortunate former surgeon had access to his US Army pension and he wasn’t judged to be dangerous, he was able to live in relatively comfortable quarters and to buy and read books while he was confined. Rather poignantly, he was often visited by the widow of the man he had killed, and she provided him with a constant supply of books. It was there at Broadmoor that Minor – probably through his correspondence with London booksellers – heard about the call for volunteers in Murray’s April 1879 Appeal. Reading through his large personal library of antiquarian books, Dr. Minor started to compile quotations illustrating the way particular words were used, and before long he became one of the new dictionary’s most effective and prolific volunteer contributors,

The final years of the lexicographer and the madman, and the publication of the OED

Work on the new dictionary was slow, despite contributions from Dr. Minor, the greater English-reading public, and the surviving tireless Sub-editors. Mr. Murray and Dr. Minor became friends. Finally, five years after the great appeal, Murray and his team of dictionary helpers – having managed to get to “Ant” – started to publish the dictionary in unbound fascicles, under the name A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles; Founded Mainly on the Materials Collected by The Philological Society. The first volume, words from A to Ant, appeared in print in 1884 at Oxford’s Clarendon Press. The 352-page volume cost 12 shillings 6 pence and sold 4,000 copies.

It would be another seven years before Murray first met Minor in person and learned about his murky history, in January 1891.

In 1895, the title The Oxford English Dictionary was first used unofficially on the covers of the series, although the original longer official title was still printed on the title pages of the volumes. A few years later, Murray acknowledged Minor’s enormous contributions to the dictionary and complimented him, stating, “We could easily illustrate the last four centuries from his quotations alone.”

Devoting most of his waking days to the work of the dictionary, Minor’s mental health continued to deteriorate, and in 1902, suffering nightly delusions that he was being abducted from his rooms and conveyed to places as far away as Istanbul and forced to commit sexual assaults on children, he cut off his own penis using a knife he had used in his work on the dictionary. Murray, concerned about his colleague’s condition, campaigned on his behalf for his release, which was finally granted to Minor in 1910 on the orders of the then Home Secretary, a 35-year-old Winston Churchill.

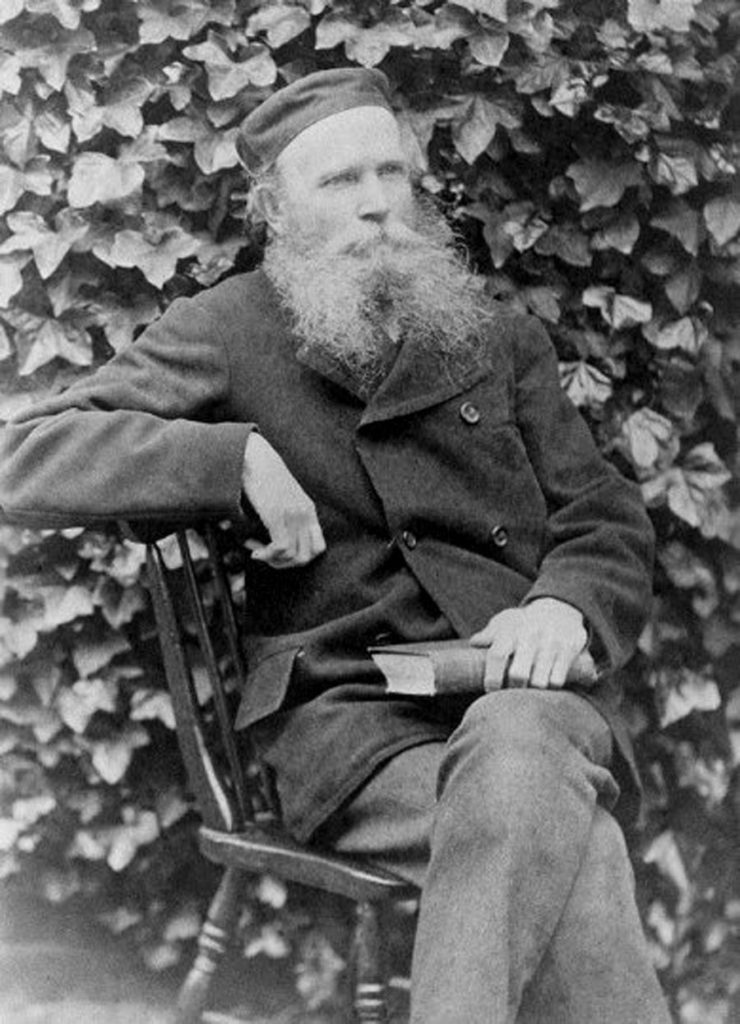

Murray spent the rest of his days in Oxford, continuing to receive and process a staggering volume of materials and completing about half of the dictionary by the time of his death – sections A–D, H–K, O, P, and T. Despite his devotion to the dictionary, which was recognized by his knighthood in 1908, Sir James remained a relative outsider in Oxford, never fully taking part in university academic life. Murray was never made a Fellow of an Oxford college, and only received an Oxford honorary doctorate the year before his death.

As for the OED itself, the 125th and last fascicle covered the words from wise to the end of W and was published on 19 April 1928; the full dictionary in bound volumes followed immediately, running to twelve volumes, with 414,825 words defined and 1,827,306 citations used to illustrate their meanings. Sadly, Sir James did not live to see the completion of his great work; he had died in 1915.

In 1998 Simon Winchester wrote a book called The Surgeon of Crowthorne (published in America as The Professor and the Madman), which chronicled Minor’s later life and told the story of how Murray and Minor worked together to advance the OED. (Incidentally, the title of the American book and subsequent movie was something of a misnomer, since Murray was never a Professor. But that didn’t bother either Harper or Hollywood.) Mel Gibson bought the movie rights for the book the same year it was published. The film adaptation, with the same name as the American book, was released in May 2019.

*****

Founding editor James Murray was also reluctant to include scientific terms, despite their documentation, unless he felt that they were widely enough used. In 1902, he declined to add the word “radium” to the dictionary.