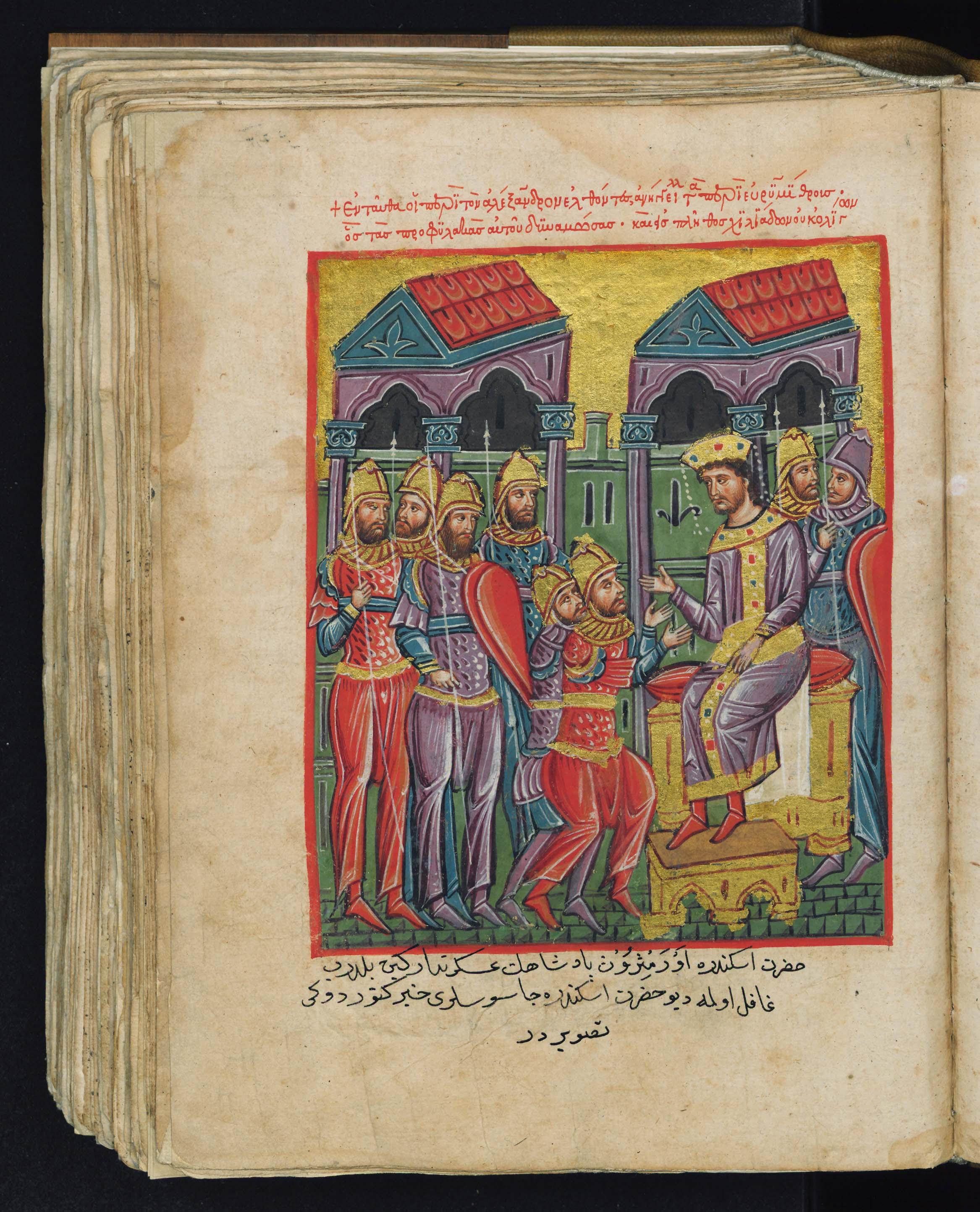

Miniature of the “Alexander Romance”, a 14th-century book, late Byzantine period / Wikimedia Commons

We use them all the time: adjectives that originally came from real or proper names. In its simplest form — a French kiss, a Shakespearean turn-of-phrase, a Freudian slip — it seems only fair that a proper name should retain its proper capitalized status when it steps out as an adjective. However, a word can lose its initial luster when an adjective starts to assert its own “improper” identity and emancipate itself from its lofty namesake. “In August, a teenager from Iowa cooked dozens of similarly Lilliputian pancakes for her chickens,” reported New York magazine yesterday. Here, the miniaturizing adjective named after Jonathan Swift’s fictional island was allowed to keep its proper L. “Toronto tries to simplify byzantine PATH map,” the Toronto Star said in a headline on Monday, with the Canadian paper’s editors denying byzantine its capital B despite the adjective taking its name from a real but ancient empire. Why is there a difference in treatment between the two?

It seems that proper adjectives fall into two broad categories: 1) those that remain firmly attached to their namesakes in meaning and association, no matter how extensive their own usage (e.g. nationality adjectives like American or English); and 2) words that assume a new meaning in their adjectival form, by moving away from the core meaning of their original proper names and then by overshadowing them in their usage. Take the word chauvinistic: originally derived from Nicolas Chauvin, a character in Théodore and Hippolyte Cogniard’s 19th-century play La Cocarde tricolore who was noted for his excessive patriotism and devotion to Napoleon, the word first described a quality of exaggerated, blind nationalism. But it began to transform over time, extending in the late 19th century in communist jargon to capture a racist attitude, and then assuming a sexist role in the late 1960s. So the chauvinistic man of today no longer carries the capital C of an overly devoted fictional Napoleonic disciple who barely qualifies as a chauvinist. Other adjectives that have long since shed their initial caps and proper name associations are gargantuan, quixotic, titanic, caesarian, draconian, epicurean, galvanic, herculean, italic, mercurial, oedipal, pyrrhic, spartan and voltaic.

The problem comes when an adjective falls somewhere between two stools — when, like a toddler recognizing her own identity, a word starts to detach itself from its namesake without establishing a distinct and different enough definition to make it stand on its own lower-case feet. Byzantine is one such word: the extent of its movement away from its namesake is ambiguous. Most dictionaries still grant the adjective a capital ‘B’ in honor of the empire it once named. Oxford Dictionaries does just that when it gives the modern second definition: “(of a system or situation) excessively complicated, and typically involving a great deal of administrative detail.” However, at least two modern dictionaries are brave enough to give the word its independence, granting the adjective a small ‘b’ for its 21st-century definition. American Heritage Dictionary (in its newest, 5th edition from 2011) gives this as one of its usage examples: “a bill to simplify the byzantine tax structure.” Similarly, the Macmillan Dictionary offers “the byzantine power structure of the old department.”

Biblical suffers from the same ambiguity: you’ll see it with both capital and small ‘b’s in a range of contexts, whether it refers to the proper-named religious text or to something much more generic happening on a very large scale. Just last week, in an article about modern technology unlocking the secrets of a damaged ancient scroll, the New York Times reported that “working with biblical scholars in Jerusalem, [computer scientists] have used a computer to unfurl a digital image of the scroll.” (I’m sure those scholars study ancient religious texts and aren’t just very big people.) Similarly, in today’s Belfast Telegraph, under the headline “Abortion issues and biblical teachings,” Donald Gale “tries to justify an anti-abortion stance by quoting the Bible.” “A biblical plague of hundreds of super beetles have forced a woman to flee her home,” cried a horrified Mirror today, acknowledging with a small b that the army of invading creatures was biblical only in its size. And yet the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette a couple of days ago observed “a challenge of Biblical proportions for Team Europe” in its report of a hockey game. And earlier this month, Canada’s CBC reported that “a flock of ancient and Biblical sheep are ready to return to Israel after stops in Hamilton and Abbotsford, B.C.” Is that Abbotsford Before Christ, of Biblical times, I wonder? Those ancient sheep will feel right at home there.

Thanks, Bill R, for the question.

***