It’s one of those things that some people care about and some don’t: if and when you should say “all of”, and when just “all” will do. Is there a rule about this? Well, it’s more of a well-established recommendation than a firm directive, and it’s generally understood that by following this rule of thumb you keep your prose sounding more lean and poetic. Continue reading

Category Archives: Words, phrases & expressions

An American-British experiment: some interesting results …

Thanks to everyone who participated in our Ameri-Brit “which–that” exercise (see Glossophilia’s post from January 20th; the exercise is shown again below). That was a tough one! There didn’t seem to be a really definitive difference in understanding or usage between the Brits and the Americans on this subject, as I thought there might be, but there was a fairly firm pattern emerging. (Update, Feb 5: my apologies to those whose answers weren’t taken into account when this was published; some of the comments were hidden/unavailable until now.) Continue reading

Two tattoos, one taboo …

When you hear the word tattoo, do you think of skin pictures or of marching band extravaganzas? Maybe both, if you’re a British drumming soldier with a body-load of tats … Curiously, the two meanings of this unusual word have completely different origins in both time and place — and quite interesting stories behind their respective definitions. It’s not too surprising that they have nothing to do with each other (except perhaps that they’re both, loosely, forms of artistic expression, and soldiers often have lots of tattoos), but it is odd that they evolved eventually into the same word. And did you know that tattoo and taboo have more in common with each other than the fact that they rhyme? Here’s the scoop on tattoo, tattoo and taboo. Continue reading

An American-British usage experiment: please participate!

Glosso readers: may I ask for your help and input for a little usage exercise? It’s fun, and it shouldn’t take more than a couple of minutes. (And I mean that in the British rather than the American sense.) I’m trying to determine whether a certain usage trend is disappearing in the UK while remaining healthy and robust in the U.S.

Please read these four sentences, which are nearly but not quite identical, and then answer the questions that follow (in the comments section below). There’s no “right” or “wrong” here: just answer honestly and without too much thought. Next week we’ll look at the results and what they might suggest.

Many thanks for your participation!

Sentences:

A) “Looking at the three designs, I was most drawn to the round one that bled outside the page border; however, I liked the square one too.”

B) “Looking at the three designs, I was most drawn to the round one which bled outside the page border; however, I liked the square one too.”

C) “Looking at the three designs, I was most drawn to the round one, that bled outside the page border; however, I liked the square one too.”

D) “Looking at the three designs, I was most drawn to the round one, which bled outside the page border; however, I liked the square one too.”

Questions:

Q1: Are you American or British? (Or Australian, Canadian or other English-speaker?)

Q2: Do any of the sentences look strange or “incorrect” to you? (Let’s not give any explanations until we’ve gathered some reactions; we’ll examine the whys and wherefores in a follow-up post.) If so, please specify which sentence(s) you’d be inclined to edit.

Q3: Can you tell from any of the sentences how many of the three designs are round? If so, please identify the sentence and the number of round designs.

* * *

Je suis X, we are Y: the power of identification and the rule of three

On that fateful September day in 2001, in the aftermath of the attacks on the U.S. that would change history, an anchorwoman on France’s main TV news show, Nicole Bacharan, uttered these words: “Tonight, we are all Americans.” It was a sentiment felt and understood keenly around the world, and the phrase was printed on the front page of the French newspaper Le Monde the next day. Almost 40 years earlier, in June 1963, U.S. President John F. Kennedy declared during a speech in West Berlin his country’s support for the new western nation now standing in the shadow of the recently erected Berlin Wall. “Ich bin ein Berliner,” Kennedy stated. “I am a Berliner.” The 1960 epic movie Spartacus reaches its emotional climax when a multitude of slaves, asked by Crassus to give up their leader by pointing him out from the crowd, each stands up to proclaim: “I am Spartacus.” Now fast-forward to the present day, after an unthinkable massacre in Paris that took the lives of 12 journalists, and we all stand together in disgust and protest by uttering three simple French words: “Je suis Charlie.” Continue reading

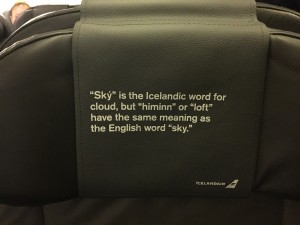

Icelandic fare from Icelandair

Did Benedict Cumberbatch (aka Alan Turing) coin the term “digital computer”?

Did Alan Turing coin the term “digital computer”? There’s a heady set of questions here: when was the modern-day computer invented, and was Turing its father — in its conception, its realization and/or its naming? The movie The Imitation Game, set in England during the Second World War, is all about the British mathematician, logician, cryptanalyst, philosopher, mathematical biologist, pioneering computer scientist, and marathon and ultra-distance runner, and it does give us a clue. There’s a significant moment in the movie when Turing (played by the ubiquitous Benedict Cumberbatch) explains to his friend and fellow code-breaker Joan Clarke (Keira Knightley) his theory of computing and his new invention — a machine called Christopher. (Watch the movie to find out the reason for the name, and what exactly Christopher was built to do.) Here’s that moment, and it isn’t really a spoiler:

Auld Lang Syne

“Auld Lang Syne” is one of Scotland’s greatest gifts; sung around the world from Times Square to Tokyo, the song recalls those we’ve loved and lost and beloved memories of days gone by, as well as giving those who sing it a sense of belonging and togetherness that looks forward to better times. Robert Burns wrote a poem in 1788 and set it to the tune of a traditional folk tune. Soon after the song was penned, it became a Scottish custom to sing it on New Year’s Eve (or what the Scots call “Hogmanay”) — a tradition that soon spread to other parts of the British Isles. Then, as the Scots and Brits started to emigrate around the world, so the song and the tradition travelled internationally. “Auld Lang Syne” translates into English as “old long since” or, more colloquially, “long long ago”, “days gone by” or “old times”. So the first line of the chorus — “For auld lang syne” — can be loosely translated as “for (the sake of) old times”, and indeed those words are often added to the final line of the chorus (ie. “for the sake of auld lang syne”) for this reason.

Here is Burns’s original poem, and below is the song as we sing it around the world today.

Auld Lang Syne

Should auld acquaintance be forgot,

and never brought to mind ?

Should auld acquaintance be forgot,

and auld lang syne ?

CHORUS: Continue reading

When the definite article isn’t very definite

“Lennon, Mailer’s friend and authorized biographer, told me that McAlice, whom he described as having “Joycean gifts,” once took the bus to Provincetown to visit Mailer.” — Boston Globe

The flu normally lasts a week, sometimes two. But if that time comes and goes and you’re still miserable and showing symptoms, head to the doctor.” — Kansas First News

“If counting down the last minutes before the new year lying on the couch in a blissful food coma seems like your style, consider one of these celebratory meals.” — Sacramento Bee

The is our definite article: we use it to refer to a specific thing (i.e. a noun) whose identity is clear to everyone reading or listening because of logic, common assumption, or a clause that explains it. “Please take the chocolate biscuit.” “I don’t like the hat she’s wearing.” But curiously there are times when we use the and we’re not being specific, as in the press examples above. Why didn’t McAlice take a bus (since we have no idea which bus he actually took)? Shouldn’t the Kansas First News be directing us towards a doctor (surely we can’t all go to the same one)? How does the Sacramento Bee know which couch is our favorite? Continue reading

Baubles of Britishisms – Boxing Day

Glosso’s advent: baubles of Britishisms. Coda:

Boxing Day.

(See Glossophilia’s earlier post on Boxing Day)

Zed zed zed zed zed zed zed zed zed zed zed zed zed …

(See Glossophilia’s earlier post on the language of slumber)

* * *