In the subject line of a recent press release, we announced that the pianist “Alessio Bax summers on three continents.” A couple of journalists raised their proverbial eyebrows at the word summer stepping out so nakedly and brazenly as a verb. Is this a horrid case of “verbing”, the unseemly practice of making verbs out of nouns that Benjamin Franklin described as “awkward and abominable” in the late 18th century (and which Glossophilia discussed in an earlier post, “A-verbing we will go”)? Or are we allowed “to summer” as wistfully and prettily as Jay Gatsby did in West Egg back in the 1920s? Continue reading

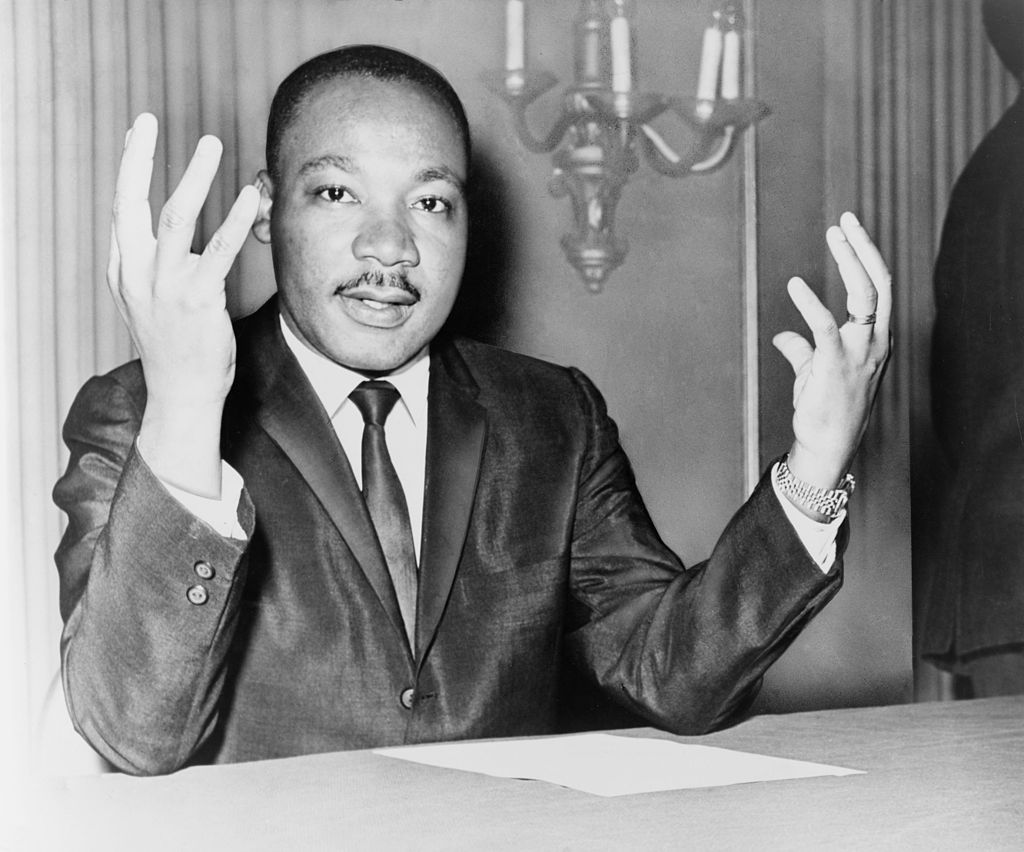

A source for Martin Luther King Jr.’s quote about faith and the staircase?

“Faith is taking the first step, even when you don’t see the whole staircase.”

When you search for that sentence on Google, you’ll get about 3,700,000 results — most of which attribute the statement (sometimes as a paraphrase) to Martin Luther King Jr. But can anyone find a source for that citation? I have searched on the King Institute web site — probably the most comprehensive collection “of King’s most significant correspondence, sermons, speeches, published writings, and unpublished manuscripts” — and found nothing resembling that sentence.

Can anyone shed any light on the history of this famous quotation?

Many thanks to Bronwyn for raising this interesting query.

***

Voir dire: to see them say, or to tell the truth?

If you’re an American and you’ve ever served on a jury — or at least been through the jury selection process (as I’ve done in the last couple of days) — you’ll be very familiar with the term voir dire. It’s the name (at least in America) of the process all prospective jurors have to go through to be selected to serve on a particular trial. And the attorneys asking all those probing questions might well explain by way of introduction the origins and meaning of that curious name, voir dire, as a translation of the two modern French verbs: “to see [them] say.” At which point, you might as a prospective juror want to jump up from your seat and shout “Objection!” (Or you might not, since you probably don’t want to be rejected from the jury for being a jerk.) Continue reading

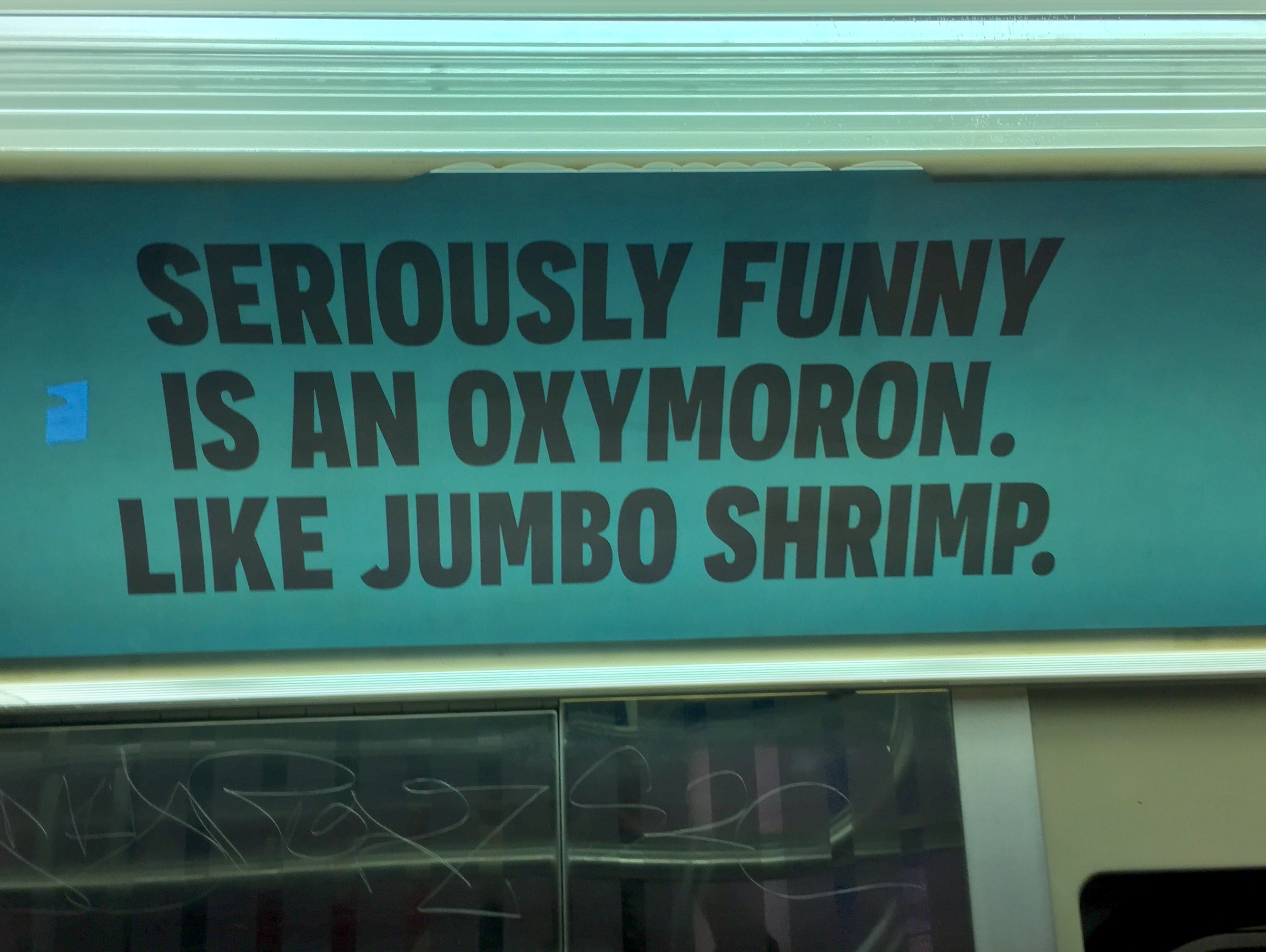

Oxymoron — and other oxymora

It’s inspiring to see grammar lessons on the New York subway, especially when your express train is running on the local track. Now everyone who took the A train on the C line last week knows what an oxymoron is. And just in case you’re still not sure what the ad pictured above means (because shrimps aren’t always tiny, are they?): it’s a figure of speech — an oxymoron — in which apparently contradictory terms are joined together to emphasize the very paradox of their conjunction. It’s often used nowadays more loosely to mean “contradiction in terms,” which is literally what it is. Oxymoron is in fact an oxymoron itself, derived from the Greek word oxus, meaning “keen or sharp”, combined with moros, which means “foolish”. Continue reading

Verbs born of names

What do the following verbs — all (except one) in fairly common modern usage — have in common? Clue: they all started their lives in the English language with capital letters (and a few of them still carry their initial cap in deference to their namesakes). Can you think of any others? Continue reading

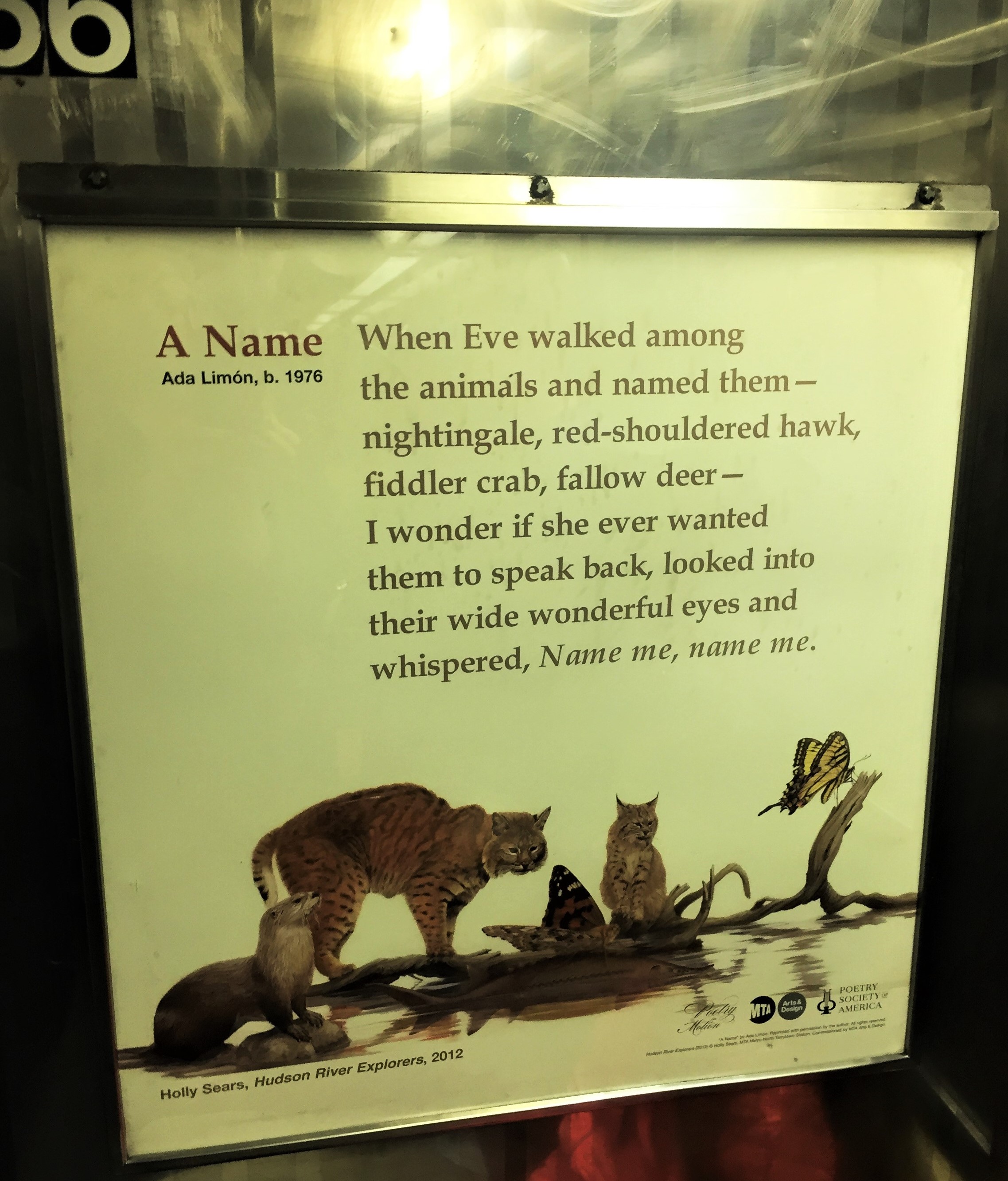

Poetry in Motion: “A Name” by Ada Limón

A sonnet on William Shakespeare’s 453rd birthday

Sonnet 98

From you have I been absent in the spring,

When proud-pied April dress’d in all his trim

Hath put a spirit of youth in every thing,

That heavy Saturn laugh’d and leap’d with him.

Yet nor the lays of birds nor the sweet smell

Of different flowers in odour and in hue

Could make me any summer’s story tell,

Or from their proud lap pluck them where they grew;

Nor did I wonder at the lily’s white,

Nor praise the deep vermilion in the rose;

They were but sweet, but figures of delight,

Drawn after you, you pattern of all those.

Yet seem’d it winter still, and, you away,

As with your shadow I with these did play.

— William Shakespeare, born on this day in 1564

* * *

Low tea or high tea? Know your teas … (on National Tea Day)

I rarely hear the expression “low tea” any more. But if I do, I’m transported back to a specific time every weekday afternoon at my boarding school in the English countryside when we would sip warm tea and dip our dry Rich Tea biscuits (and occasionally cake, if we were lucky) into our cups at the end of a long school day. Low tea was, for many, the high point of the day; long were the minutes spent waiting in class for the school bell to ring out, heralding the arrival of caffeine-and-sugar-time. “High tea” was a different story, and came a couple of hours later.

On British National Tea Day, let’s look at the origin and history (and widespread misunderstanding) of the terms “low tea” and “high tea”, and find out just what is eaten at what time on each occasion, and where the names came from. Was it the tides, the time of day, or something to do with the quality or class of the food prepared? Continue reading

Answer to yesterday’s quiz: the most meaningful word in the English language?

Yesterday Glosso asked the following: “Oxford English Dictionary editors have just revealed the English word with the most meanings: it has 645 different usage cases for its verb form alone. And that’s just when it’s a verb. Can you guess what the word is?”

The answer is “run”. As in, to run a mile. To run out of ideas. A play runs on Broadway; he has the runs. To run for a bus, or to run for President. A run for your money, or a run on the bank. Running an idea up the flagpole, running with this suggestion. And the list runs on …

“The copious definitions of “run” featured in the OED’s upcoming third edition begin with the obvious, “to go with quick steps on alternate feet,” then proceed to run on for 75 columns of type. This entry, in all its girth, took one professional lexicographer nine months of research to complete. How could three little letters be responsible for so much meaning?” Read the full story about this new Guinness World Record-Holder in Reader’s Digest.

* * *