Have you enjoyed some hygge this holiday season?

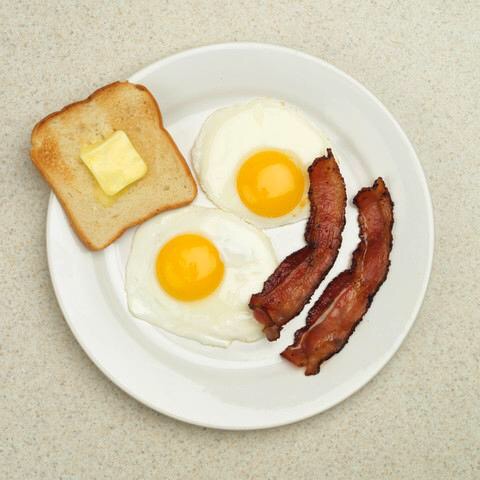

“Hygge — pronounced to sound somewhere between “booger” and “hooker” — is an apparently untranslatable concept which embodies the Nordic art of cosiness.” So explained the Financial Times in a recent article about this trendy and enviable state of well-being that apparently eludes most of us non-Nordics. “This year hygge has become a global publishing pandemic. The Danish art of cosiness has been co-opted as the latest lifestyle trend to make us feel our disorganised, overworked, over-digital and under-curated lives are utterly inadequate. It is now, after bacon and wind turbines, Denmark’s biggest export.”

The word hygge hasn’t quite yet broken the Danish-English language barrier and taken its official place in any of our official dictionaries. Perhaps that’s because, as the Financial Times argues, it’s simply untranslatable — both culturally and linguistically. Last year Justin Parkinson in the BBC’s news magazine observed: “The Danish word, pronounced “hoo-ga”, is usually translated into English as “cosiness”. But it’s much more than that, say its aficionados – an entire attitude to life that helps Denmark to vie with Switzerland and Iceland to be the world’s happiest country.”

Although the Oxford English Dictionary doesn’t yet have an entry for hygge (but do keep an eye on those new official word lists coming up in the New Year), the online Oxford Living Dictionaries does offer a relatively succinct and evocative definition for the Danish word and concept, which has definitely made its way into our lexicon: “a quality of cosiness and comfortable conviviality that engenders a feeling of contentment or well-being (regarded as a defining characteristic of Danish culture).” But do note that there are two quite different pronunciations offered up here — scroll down to the bottom of OD’s hygge page to hear them articulated. So if you are able to achieve this particular state of twee chill that seems to elude most Americans and Brits, it seems you can choose to call it either “hooker” or “hewger” — whichever kind of hygge sounds like your kind of bliss.

~~~