I’ve recently marked an anniversary of my beloved partner’s untimely death, and a new musical work addressing the subject of dying is preoccupying my professional mind. We find it hard to talk about death. Even in our commonly unfiltered world in which our every thought and observation is broadcast widely and uncensored, the subject of death and dying is one of our last lingering taboos — or at the very least an area of verbal discomfort. There are worldwide historical taboos banning the utterance of a deceased person’s name; Freud argued that such taboos stem from the fear of the presence or of the return of the dead person’s ghost. Many of us find it hard to express our condolences to the recently bereaved, or even simply to report on a person’s death: we struggle emotionally, empathically and linguistically to find the right words. And so the verb “to die” — so stark in its definitive and final form, and yet so direct and honest in its simplicity — is often and increasingly replaced by words and sayings that soften the idea of this fearful human fate that befalls us all. Apparently more pronounced among American rather than British English speakers is a growing tendency to reach for expressions such as “passed away”, “passed on”, or simply “passed” to articulate the fact that their loved ones have made their final journeys; for many, the verb “to die” is either too harsh or fails to embrace the notion of life enduring, religiously or spiritually, beyond the grave. But there are also many who prefer to address the ultimate human act of submission using the three-letter word that best describes it, honestly and unambiguously. Continue reading

Category Archives: Yanks vs. Brits

Slated, capped and palaver: what do they mean to you?

If a yoghurt is “slated for Sochi”, does that mean it failed to tickle the tastebuds of Russian athletes, or that it’s on board the supply vessel heading for the Olympic village? Hmmm. It probably depends on whether it was an American or a Brit using that rather strange turn of phrase about that particular foodstuff. (And someone did actually say that in print.) If something was capped in England, it was probably costing too much money, but to Americans it might well have been leading up to something even better. And whereas a palaver on either side of the Atlantic is much ado about nothing, it’s merely a discussion among Yanks but more of a big nuisance to the Brits.

Below are the subtly different definitions of these words determined by who is uttering them, along with some examples recently published in the media. (Except where stated, the definitions are from Oxford Dictionaries — the British-English and American-English versions.) Because the words are used differently — contextually and linguistically — by Americans and Brits, there isn’t usually any confusion or ambiguity when they’re being communicated to trans-Atlantic counterparts; indeed, at this point both meanings are pretty well understood, if not in actual usage, on either side of the pond (at least in the case of slated and capped), even if they might still give pause. To my mind, a performance that has been slated — even if it is for a future date — still sounds like something not to get excited about.

Slated:

British: “criticize severely”. Tom Service, writing about a Bruckner symphony in The Guardian, wrote that “a contemporary critic slated its ‘nightmarish hangover style’, but Bruckner’s last completed symphony contains music of sheer, breathtaking magnificence.”

American: “schedule; plan”. In an NBC News headline, some Chobani yoghurt “slated for Sochi [was] held up at U.S. customs”.

Capped:

American: “provide a fitting climax or conclusion to; follow or reply to (a story, remark, or joke) by producing a better or more apposite one”. Discussing Russia’s figure-skating team winning the gold medal in Sochi yesterday, AP sports writer Barry Wilner wrote: “It was victory capped by the freshness of Lipnitskaia.”

British: (Cambridge Dictionaries): “to put a limit on the amount of money that can be charged or spent in connection with a particular activity.” In The Guardian, the UK’s health secretary, Patricia Hewitt, was quoted as saying that “with hindsight, she wished GPs’ earnings had been capped.”

Palaver:

British: “prolonged and tedious fuss or discussion”. (Commonly used in the phrase “what a palaver”.) In the Evening Standard, gallery co-owner Tamara Beckwith, referring to selfies, was quoted as saying: “I’ve tried taking one and it was such a palaver.” Reporting on supermodel Naomi Campbell’s refusal to use her allocated dressing room for the National Television Awards, the Kildare Nationalist quoted a source telling The Sun newspaper: “What a palaver. Apparently Naomi wants something more luxurious so the team have had to scrabble around trying to find something suitable nearby.”

American English: “prolonged and idle discussion; verb – to talk unnecessarily at length.” In a report on the recent debate on creationism between Bill Nye and Ken Ham, the New Republic’s writer said: “My friend said that no, Ham wasn’t lying—he truly believed the palaver he was spewing.”

Strangely, the Brits seem to have broadened the definition of this word, which remains similar to its original meaning on American shores. According to the Online Etymology Dictionary, palaver dates from 1733 (implied in palavering), “talk, conference, discussion,” sailors’ slang, from Portuguese palavra “word, speech, talk,” traders’ term for “negotiating with the natives” in West Africa, metathesis of Late Latin parabola “speech, discourse,” from Latin parabola “comparison”. Meaning “idle talk” first recorded 1748. The verb is 1733, from the noun. Related: Palavering.”

In the news (Jan 31)

In language news this week: different ways of pronouncing Hyundai, the ‘ax versus ask’ question, whether commas are really necessary, and more. Plus a new Weird Word of the Week …

* * *

According to the BBC, there are at least three different approved ways of saying Hyundai, depending on whether you’re in South Korea, the UK or US. “The original Korean pronunciation is closest to HYUN-day (-hy as in Hugh, -u as in bun, -ay as in day, stressed syllables shown in upper case). Hyundai UK, including its adverts, has a different way of saying it: high-UUN-digh (-igh as in high, -uu as in book, British anglicisation). … Hyundai’s US operation…uses the pronunciation HUN-day (-h as in hot, -u as in bun, -ay as in day, US anglicisation).”

* * *

The ‘ax’ versus ‘ask’ question: linguist John McWhorter, in a Los Angeles Times op ed piece, asks: “Using ‘ax’ for ‘ask’ dates back to at least Chaucer, so why do we consider it illiterate today? … As a black linguist, I have come to expect that, during question sessions after any public talk I give on language, someone will ask: “What’s with ‘ax’?”

* * *

The BBC’s Mind the Gap blog identifies 10 American speech habits that grate on British ears.

* * *

Slate asks: will we use commas in the future? “In some ways commas are like ketchup and mustard. We’re glad those things exist. They surely make our french fries and hamburgers taste better. But we’d all survive without them.” Is this really so?

* * *

WWW: Weird Word of the Week:

This week’s word is batterfang: verb: To assail with fists and nails; beat and beclaw. Etymology unknown.

You say than, I say to; you say on, I say at …

Is she on heat or in heat? Depends whether she’s wearing a nappy or a diaper…

In my work as a publicist, one of my most frequent questions to journalists is: “Would you like to talk with Mr. or Ms. Musician”? My British instinct is to suggest that they talk or chat to someone: that’s what we do in England, and not just when we’re telling someone off. But this turn of phrase does have a reproachful or condescending whiff about it; there’s even a corresponding noun — you give someone a “talking to” when you’re reprimanding them. The American preposition of choice in this instance — with — lends the conversation a much more egalitarian air, and even Brits are now beginning to talk with rather than to each other, especially if they’re trying to be more politically correct.

It’s amazing what a difference a little preposition can make. Here are some more examples of Brit-prep-Ameri-prep that keep us at prepositional odds with each other.

Different from is cool on both sides of the ocean. “That Londoner is no different from that New Yorker.” However, Justin Bieber would claim that his haircut is different than Miley Cyrus’s do, whereas Downton Abbey’s Dowager Countess would be the first to point out how different her manners are to those living down below stairs.

* * *

David Beckham’s sons probably play football in their school team; one of Andy Pettitte’s sons, Joshua, was invited to play on a famous team – the Yankees.

* * *

Prince rocks out on, over or during the weekend; Prince Harry just parties at the weekend (as well as during the week…).

* * *

One of Her Majesty’s corgis is on heat; the Obamas’ Bo is checking out the bitches in heat…

* * *

I’m planning to enrol on the British Airways fear-of-flying course; pot-growers have enrolled in Oaksterdam University, America’s first cannabis college.

* * *

Kanye West and Kim Kardashian named their daughter either for her dad’s sense of direction or after the airline on which you used to fly smart; Prince George was named after one of his royal ancestors (probably not the mad one).

* * *

Benedict Cumberbatch can safely describe the character of his TV detective as the opposite to Idris Elba’s, and Luther is the opposite of Holmes; Columbo is the opposite of — and only of — Law & Order’s Detective Benson.

* * *

Stevie Wonder just called — at my office number; Mick Jagger, when he missed me, tried to call me on my number.

* * *

David Cameron, as well as being Britain’s Prime Minister, is the Member of Parliament for Witney, his local constituency; Barack Obama, before becoming President of the United States, was a Senator from Illinois.

* * *

And more informally, but increasingly: Taylor Swift is probably really excited for the Grammys; nominee Sir Simon Rattle is no doubt excited about them…

* * *

In the news (Jan 24)

TGIF: That Gerund Is Funky. Words and language in the news this week.

Plus the start of a new weekly series: WWW: Weird Word of the Week

On National Reading Day in the U.S. (Jan 23), Jon Stewart describes what a book is on the Daily Show. (Thanks to Grammarly on Facebook.)

Whistle while you work it

“All the world is perpetually at work, only that our poor mortal lives should pass the happier for that little time we possess them.” — Temple

Most of us work. It’s what we do for much of our waking lives. In fact, the notion of work is so embedded in our psyche that the very word pervades all aspects of our lives — even when we’re at play. The word with so many definitions (it takes up several pages of the OED) has never been confined to just its core meanings of toil, labor and employment; more than representing simply the opposite of play, it embraces countless notions of intention and activity in as many different guises. Work takes a proud place in the Oxford Dictionaries’ list of the 1,000 most frequently used words. And recently it has begun to work its way idiomatically even further and more pervasively into the lingo. But let’s start with our more traditional understanding and use of the word.

“Fodder, a wand, and burdens, are for the ass; and bread, correction, and work, for a servant.” — Ecclesiasticus 33:24

Even in its core context — that of employment — work can refer to so many of aspects of its own self, showing off its versatility before it’s even left the workplace. Continue reading

You say soda, I say pop; you say soda water, I say club soda; what the fizz?

If an Englishman asks you for a soda, he most probably means, specifically, soda water, or what his friend across the ocean might refer to as a club soda. But an American asking for a soda likely has another idea in mind: on these shores it usually indicates any sort of carbonated soft drink, whether it be a Pepsi, ginger ale, 7-Up, or — as the Brits might generalize — a “fizzy drink”.

But what’s the difference between British soda water and “fizzy water” (as the Brits would say when I was younger — now more often and elegantly referred to as “sparkling water”) or “seltzer”, as the Americans usually name their fizzy H2O?

In the UK, soda water contains bicarbonate of soda, which gives it a specific flavor and differentiates it from plain carbonated or sparkling water (or seltzer), making it popular as a mixer in drinks like whisky and soda or Campari soda.

In the U.S., carbonated water was known as soda water until the Second World War because of the sodium salts added as flavoring and acidity regulators to mimic the taste of natural mineral water. In the ’30s, during the Depression, it was sometimes called “two cents plain”, being the cheapest drink offered at soda fountains. The names sparkling water and seltzer water flourished during the ’50s, with the latter being a classic “genericized brand name”, much like the modern generic kleenex, hoover and biro, which all originated as trademarked names. Seltzer derives from the German town Selters, renowned for its mineral springs from which naturally carbonated water has been commercially bottled and shipped since the 18th century. Seltzer water doesn’t usually have added salts, whereas the American club soda (another brand-name-turned-generic) still often retains sodium salts, making it more akin to the British soda water. However, seltzer or seltzer water isn’t used — or even really known — in Britain and most Commonwealth countries.

Nowadays in the U.S., soda has come to mean any type of sweetened, carbonated soft drink (with soft drinks so called — across standard English — to contrast them with “hard” or alcoholic drinks). The Online Etymology Dictionary gives this potted history of the word. “Soda meaning “carbonated water” is first recorded 1834, a shortening of soda water (1802) ‘water into which carbonic acid has been forced under pressure.’ ‘It rarely contains soda in any form; but the name originally applied when sodium carbonate was contained in it has been retained’ [Century Dictionary, 1902]. Since 19c. typically flavored and sweetened with syrups. First record of soda pop is from 1863, and the most frequent modern use of the word is as a shortening of this or other terms for ‘flavored, sweetened soda water’.”

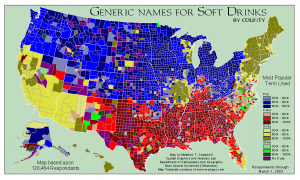

However, just to confuse matters even further: the name for fizzy soft drinks in the States varies by region. Soda and pop are the two most common American names for this broad category of beverage, but there are others, including soda pop, the British fizzy drink, and even coke, which is used generically in the South. And the word Americans choose to name their fizzies is most associated with their geographic origin or location, rather than their age, race or socio-economic status. Go fizz.

Soda is most common on the East and West Coasts, as well as in St. Louis and Hawaii. Pop tends to be the name of choice in the Midwest, the Pacific Northwest and Mountain West. According to the Online Etymology Dictionary, pop meaning “flavored carbonated beverage” dates back to 1812, and was onomatopoeic in its origin. Robert Southey in a letter of that year described his “new manufactory of a nectar, between soda-water and ginger-beer, and called pop, because ‘pop goes the cork’ when it is drawn.” In the South, coke (or cola) is used generically to name any type of soft drink—not just colas (for which coke is a common nickname) or their most famous brand representatives, Coca-Cola and Pepsi. The reason for this is quite possibly that Coca-Cola’s headquarters are located in Atlanta, Georgia, a southern state. Coke is also heard generically in neighbors of the southern states, such as New Mexico and Southern Indiana, as well as in specific areas like Trinity County, California and White Pine County in Nevada.

Popvssoda.com has published a map of the U.S. showing the generic names for soft drinks by county.

If you want further facts on this fabulously fizzy phenomenon, here’s Wikipedia‘s list of brand names of soft drinks listed by their country of origin. Aren’t you dying to know what exactly Pritty, Juizee Pop, Pschitt, Battery and Semtex (sic) are — and where they are drunk?

You were fired, or you GOT fired?

When something happens to us and we’re reporting that action in a passive (“I was eaten alive”) rather than active (“they ate me alive”) sense, we’re usually content to use the verb “to be”, with whatever conjugation is called for: “I was taken”, “they were scolded”, “we’re going to be enlightened”. It’s a tense or form that tends to be preferred when we’re focussing on what has been done to the thing or person in question rather than on whoever or whatever performed the action — or when the agent of the action is unknown or simply unimportant.

But increasingly, at least colloquially, we’re reaching for the verb “to get” when using the passive sense — and especially when something especially bad or good is happening to the subject and when that subject is a person. When Donald Trump points his finger at you symbolically, you’re perhaps more likely to exclaim “I got fired!” than to declare the more neutral “I was fired”. “She got screwed over” packs more of a proverbial punch than the gentler “she was screwed over”; similarly, to say that “he got promoted” or that “she got seduced” puts more emphasis on the animate subject and on the positive action, despite it being expressed in the passive voice.

According to Arika Okrent, in her article “Four Changes to English So Subtle We Hardly Notice They’re Happening” in The Week (June 27, 2013), “the get-passive goes back at least 300 years, but it has been on a rapid rise during the past 50 years. It is strongly associated with situations which are bad news for the subject — getting fired, getting robbed — but also situations that give some kind of benefit. … However, the restrictions on its use may be relaxing over time and get-passives could get a whole lot bigger.”

In Junichi Toyota’s Diachronic Change in the English Passive, he makes an important observation, according to Rose Rittenhouse’s review of the book, arguing “that the get-passive overwhelmingly focuses on an animate subject that is more involved in the action affecting it.” Clarifying this theory in some detail, Anja Wanner’s book Deconstructing the English Passive outlines several restrictions or identifying qualities of the get-passive, as discovered and described by various linguists in the last few decades:

- “The get-passive receives a more dynamic interpretation than the be-passive (Quirk et al., 1985)”

- “The get-passive often has adversative — and sometimes beneficial — interpretation (Chappell, 1980; Carter and McCarthy, 1999), and reflects the speaker’s attitude towards the event (Lakoff, 1971). This characteristic of the get-passive has been traced back to its very beginning in the 17th century (Givon and Yang, 1994).”

- “The subject of the get-passive is generally animate and, although underlyingly the object of the verb, is interpreted as somehow responsible for the action (Arce-Arenales, Axelrod and Fox, 1994; Givon and Yang, 1994; Huddleston and Pullum 2004). In a sentence like Mary got shot on purpose, Mary is not the agent of shot, but she is considered to be somehow responsible for the event (having brought the event about through some action of hers). This is also known as the “secondary agent” reading (Roeper, 1987).”

- Finally, and perhaps most interestingly for some, “the get-passive is used more often in American than in British English (Sussex 1982) and is also acquired earlier in American English than in British English (Meints 2003).”

It’s interesting that our growing tendency (by using the get-passive with more frequency — especially in America) seems to be turning the passive back into a more active voice, perhaps suggesting that the latter is a more natural expression and reflection of the way we perceive and view our world, and that the passive is losing its place in the language. If many linguists and style guides had their way, we would steer clear of the passive voice altogether: it’s been widely discouraged for some time now. In 1926 Fowler advised against it, claiming that doing so “sometimes leads to bad grammar, false idiom, or clumsiness.” As Thomas Hobbes said in 2001, “In general, the passive voice should be avoided unless there is good reason to use it, for example, in this sentence, which focuses on ‘the passive voice’.” (The Blackwell Guide to the Modern Philosophers).

Got milk? Got the get-passive?

Catching zeds, and the language of slumber

When and why did we start using zzz to refer to sleep? How long have we been catching zeds (or what Yanks call zees), and since when have we been getting our 40 winks?

The OED lists one definition of z (“usually repeated”) as “used to represent the sound of buzzing or snoring”, and it was indeed a case of onomatopoeia that first linked the letter z — or multiple zzzzzzs — to sleeping by approximating the sound of snoring. The American Dialect Society’s Dialect Notes, published in 1918, lists “z-z-z” as “the sound of whispering or snoring, and 1919’s Boy’s Life, the Boy Scouts’ yearbook, gives “Z-z-z-z-z-z-z” as the title of a joke about that most supersonic of sleep sounds. This onomatopoeic use of z’s — which later came to signify, more generally, the state of slumber — was popularized by its use in early comic strips and comic books, for example in Schulz’s “Peanuts” cartoon series. In fact, a single Z in a speech bubble is enough nowadays to indicate that a character is asleep, and this is no longer confined to just the English language: as Wikipedia explains, “Originally, the resemblance between the ‘z’ sound and that of a snore seemed exclusive to the English language, but the spread of American comics has made it a frequent feature in other countries. An exception to this is in Japanese manga, where the usual symbol for sleep is a large bubble coming out of the character’s nose.”

And why “40 winks”, meaning a short sleep or nap? It’s not clear where or when the actual expression originated, but the number 40 is known to have been used historically to signify a great or indefinite number — hence the Biblical “40 days and 40 nights” and other numerous references; as argued in The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia,” edited by James Orr in 1915, “it may have originated, partly at any rate, in the idea that 40 years constituted a generation or the period at the end of which a man attains maturity, an idea common, it would seem, to the Greeks, the Israelites, and the Arabs.” Add the informal meaning of wink as a very short period of time, especially in the context of lack of sleep (as in, not being able to “sleep a wink”), and suddenly “40 winks” makes perfect sense. The Online Etymology Dictionary attests the expression “40 winks” from 1821, and speculates that its early use might have been associated with, and perhaps coined by, the eccentric English lifestyle reformer William Kitchiner M.D. (1775-1827).

Other colloquial words and expressions for slumber are cat nap (noun), to doze or doze off (verb), to nod off (v), shut-eye (n), snooze (v & n), and going bo-bos. Cockney Rhyming Slang gives us soot (Sooty and Sweep = sleep) and Bo Peep — the latter possibly giving rise to the suggestion, cooed persuasively and desperately to British babies, of “going bo-bos”…

“Goodnight, sleep tight, and don’t let the bed-bugs bite.” Tight in this context refers not, as some contend, to ropes tied tautly across early bedsteads, but instead to the adverb tightly, defined by the OED as “soundly, properly, well; effectively”; indeed, that dictionary’s first definition of tight itself is “soundly, roundly; = TIGHTLY 1. Now chiefly in colloq. phr. (good night) sleep tight, a conventional (rhyming) formula used when parting for the night or at bedtime.” The bed-bugs can probably speak for themselves.

To Sleep

O soft embalmer of the still midnight,

Shutting, with careful fingers and benign,

Our gloom-pleas’d eyes, embower’d from the light,

Enshaded in forgetfulness divine:

O soothest Sleep! if so it please thee, close

In midst of this thine hymn my willing eyes,

Or wait the “Amen,” ere thy poppy throws

Around my bed its lulling charities.

Then save me, or the passed day will shine

Upon my pillow, breeding many woes,

Save me from curious Conscience, that still lords

Its strength for darkness, burrowing like a mole;

Turn the key deftly in the oiled wards,

And seal the hushed Casket of my Soul.

— by John Keats

TGIF: That Gerund Is Funky (Dec 27)

As 2013 draws to a close, we’ve got lots to celebrate about it — like the use of the word selfie, and other words of the year. The Russians haven’t just banned discussions about homosexuality: they also won’t let anyone mention obscene terms for genitals or women of easy virtue. The Church gave a nod to Mexican languages; the Finns don’t like the way iPhone is spelled. And we learned some important new facts: like the words for horse-eating, 3-letter extensions to words in Scrabble, and French kissing in France …

* * *

What do selfies, Suarez and Seamus Heaney have in common? The same as Bieber, bitcoins and Breaking Bad . . . They all appeared in “top words of 2013” lists. “PRIVACY. Selfie. Geek. Science. Four dictionary publishers each selected one of those words as its word of the year for 2013. But it’s tough to catalog the preoccupations of the year in a single word. There were many flying around that seemed to capture a moment, an emotion, a thought, a new way of doing or describing things, or the larger zeitgeist. Some were new, some not so new, but they all seemed to say something about the times. Here are a few …”, the New York Times reported …

Time magazine looked more closely into Oxford’s actual word of the year, which is captured — literally — in James Franco’s pic above …

* * *

The Russian media has been given four categories of swear words that must never appear either in articles or in readers’ comments, in print or online. Newspapers and websites that fail to comply could lose their licenses. The list of unprintable words was compiled by Roskomnadzor (Federal Supervision Agency for Information Technologies and Communications) and among the categories of banned words are “obscene terms for a woman of easy virtue”. RT has the story.

* * *

Mexico’s indigenous languages get a nod from the Church. The BBC has the story …

* * *

According to Cult of Mac, Finland’s linguistic authorities — the Institute for the Languages of Finland, which rules on correct spellings, loan words and usages as the Finnish, Swedish, Romani and Sami languages develop — has decreed that the correct Finnish usage of iPhone is not iPhone, but rather Iphone or I-phone. You tell ’em, Finland.

* * *

Finally, thanks to the BBC’s list of “100 things we didn’t know last year”, we now know 22 fun facts about words and language that we didn’t know in 2012:

Horse-eating is called Hippophagy.

“Russian flu” got its name because of the Cold War rather than because it originated in Russia.

William is the surname that has decreased the most since 1901.

Haribos are so-named because of founder Hans Riegel and his hometown Bonn.

South Africa was included in the BRICS as it made for a better acronym than Nigeria.

“Lucifer” and “.” (full stop) are banned baby names in New Zealand.

Birmingham City Council blocks the word “commie” from incoming email.

Using “don’t” and “won’t” correctly in online dating messages boosts response rates by more than a third.

The French call a walkie-talkie a talkie-walkie.

Until recently the US Navy had a requirement that all official messages be sent in capital letters.

“God’s bones” was the sweariest expression in medieval times.

The French had no official word for French kissing… until now. It’s “galocher”.

Ampersand was once an actual letter which followed the letter Z in the Latin alphabet.

The first recorded incorrect use of the word “literally” was in 1769.

Polyamorous people have invented a word to indicate the opposite feeling of jealousy – compersion.

Glaswegians are starting to sound like Cockneys because of EastEnders.

In Scrabble, a Benjamin is a three-letter extension to the front of a five-letter word.

The word “get” went out of fashion in books between 1940 and the 1960s.

Amazon’s original name was to be Relentless – and the URL relentless.com still redirects to the company website.

John Wayne coined the phrase “the Big C” to avoid naming cancer.

Americans pronounce gifs as “jifs”.

A long-term lover is known as a “small house” in Zimbabwe.