“420”. Or more specifically: Four Twenty. What does that mean to you? For me, I’m transported back to a specific time every weekday afternoon at my boarding school in the English countryside when we would sip warm tea and dip our dry Rich Tea biscuits (and occasionally cake, if we were lucky) into our cups at the end of a long school day. Low tea was, for many, the high point of the day; long were the minutes spent waiting in class for the school bell to ring out, heralding the arrival of caffeine-and-sugar-time. In those days (and this will surely date me), 4.20 meant simply a number or time of day: tea-time! Its ‘higher’ connotations had yet to spread beyond the drug culture of Californian youth …

Let’s go 420, and explore the origin and history (and the truths and myths) of the term. And let’s also look at the origin and history (and widespread misunderstanding) of the terms “low tea” and “high tea”, and find out just what is eaten at what time on each occasion.

“Let’s go 420, dude!”

You have to have been hiding under a rock for the last couple of decades if you don’t know what 420 means. But ask anyone why, and the haze of uncertainty about its etymology is about as thick as the mind of a ’70s Deadhead (which is actually where the term spent much of its infancy, probably also under a rock). “Isn’t or wasn’t 420 the police dispatch code for smoking pot?” No, it’s not the dispatch code for anything. “Hitler’s birthday was April 20.” So …? “4.20pm is tea-time for pot-smokers in Holland.” Yeah, and for everyone else in the world, including the Queen of England. “There are approximately 420 active chemicals in marijuana.” There are about 315 active chemicals in marijuana, but the actual number fluctuates depending on which plant you’re using. “April 20 is the date that Jim Morrison/Jimi Hendrix/Janis Joplin [pick one] died.” Nice try, but even though they were all strongly associated with drugs and drug-taking, not one of them died on April 20.

Steven Hager, editor of High Times, traced the term 420 back to a group of about a dozen pot-smoking high-school students in 60s/70s San Rafael, California, who called themselves the Waldos. The kids first used the term in fall 1971 as part of a plan to search for a cannabis crop that was rumored to have been abandoned in a nearby forest. For this particular marijuana hunt, which was repeated on several occasions (although that crop never was never to be found), the Waldos agreed to meet at 4.20pm near a statue on the school campus before heading into the woods. The meeting time for the hunt became a general meeting time for smoking pot, and so as not to let on to unsuspecting parents or teachers, 420 became their code-word for a time to get high. As it spread beyond the school grounds, referring more generally to the art and recreation of marijuana-taking, the term began to take root amongst the dope-smoking Californians of the day — notably the Deadheads (Grateful Dead fans and followers) who were local to and associated with San Rafael. And before long, 420 was understood and used (linguistically as well as literally) by an entire generation of potheads, who have in turn passed it along to their own issue — the word, the habit, and in some cases the wacky baccy itself. Here’s a flyer that was handed out by Deadheads in Oakland, CA before a Grateful Dead concert in 1990:

The term 420 is now ubiquitous in popular culture and in the common vernacular, often with tongue in cheek or as an oblique reference to Grandpa’s medicine. Most of the clocks in Pulp Fiction are set to 4:20. (There is one watch set to 9.00.) There’s both a record label and a band called 4:20. Atlanta’s Sweetwater Brewing Company sells 420 Pale Ale and opens at 4.20pm most weekdays. A New York-based travel company, 420 Tours, sells cheap packages to the Netherlands and Jamaica. California’s Senate Bill 420 regulates marijuana used for medical purposes. In 2001, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Center for Substance Abuse Prevention published (on its web site) a document called: “It’s 4:20: do you know where your teen is?”

Nowadays, you’ll find “420-friendly” used commonly as an attribute — alongside height, education, hobbies and fetishes — by online romance-seekers in their web profiles. So if you’re looking to date a stoner, you’re in luck: just type 420 into the search-box …

Low tea and high tea

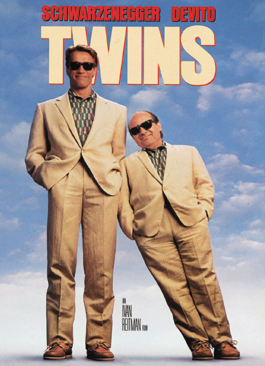

That’s not a mistake: these are fair representations of the meals “low tea” and “high tea”, names that derive not from the tides, the time of day, nor the quality or class of food prepared, but from the height of the tables at which the meals were traditionally taken.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, “tea was generally consumed within a lady’s closet or bedchamber and for a mainly female gathering.” Ladies would receive callers with their morning tea, usually “abed and bare-breasted” (from “A Social History of Tea” by Jane Pettigrew). It is generally thought that the English afternoon tea tradition was established in the early 19th century by Anna Maria Russell, Duchess of Bedford, a lifelong friend of Queen Victoria whom she served for a time as a lady of the bedchamber. The Duchess, feeling the energy low that hits us all in the late afternoon, started asking for light sandwiches and tea to be brought to her to tide her and her rumbly-tummy over between the lunchtime and evening meals. Then she invited others to join her in this afternoon repast, and so the tradition of afternoon or “low” tea was born. Ladies of the fashionable upper classes would serve a ‘low’ or ‘afternoon’ tea around four o’clock, just before a promenade in the park.

Low tea can consist of any combination of biscuits, sandwiches (cucumber please), scones with clotted cream and jam, and, most importantly, tea. It’s not so much a meal as a light and indulgent afternoon snack. (Although who would call scones with clotted cream and jam ‘light’?) “Low tea” got its name from the furniture and setting of those partaking of the late afternoon fare: in living or drawing rooms in low armchairs, with low side-tables pulled alongside them on which could be placed cups and saucers, doilies and side-plates.

High tea, on the other hand, was served at the dining table. High tea is a more substantial evening meal, usually consisting of “meat and two veg” (or a similar combination); it was the main meal put on the table at around 6 pm for the working man of the family to return home to. However, high tea wasn’t a meal just of the working class. The middle and upper classes would sometimes take a high tea in the early evening – at five or six o’clock – replacing the later evening dinner, especially if there were evening entertainments planned (much like our modern pre-theater meal) or not enough staff on duty to cook or serve the dinner feast.

For inexplicable reasons, “high tea” has persisted in modern English usage – especially in America – and is often used erroneously instead of “low tea”, which is now moreorless obsolete, to describe the traditional afternoon fare. When an American hotel or tea-house offers a “high tea” service, you can be sure you’ll be eating the equivalent – at least linguistically – of tea at the Waldorf, and not the fish and chips and mushy peas that characterized the high teas of yore.

* * * * *

Thanks to Snopes.com, High Times and the Huffington Post for the dope on 420; and Afternoon Tea and Afternoon to Remember for lessons in the history and etiquette of afternoon tea.

http://hightimes.com/entertainment/ht_admin/834

http://www.snopes.com/language/stories/420.asp#DQK60F3kSb7mEd6o.99

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2009/04/20/what-420-means-the-true-s_n_188320.html

http://www.afternoontoremember.com