Are you confused about what the word impeach actually means? Does it refer to indicting or convicting, and what are its consequences? With different meanings in different places, it’s one of those muddy words that always sounds – to my ear at least – as though it should mean something slightly different. Then there’s insurrection, the other hot word of January 2021, which despite its straightforward dictionary definition has somewhat ambiguous connotations. Here’s a quick dive into what these two words mean and where they come from.

Impeach:

“A well-constituted court for the trial of impeachments is an object not more to be desired than difficult to be obtained in a government wholly elective. The subjects of its jurisdiction are those offenses which proceed from the misconduct of public men, or, in other words, from the abuse or violation of some public trust. They are of a nature which may with peculiar propriety be denominated POLITICAL, as they relate chiefly to injuries done immediately to the society itself.”

― Alexander Hamilton

Here are the dictionary definitions: OED has it as “to accuse of treason or other high crime or misdemeanour (usually against the state) before a competent tribunal.” Merriam Webster basically agrees, without the British ‘u’: “to charge with a crime or misdemeanor; specifically, to charge (a public official) before a competent tribunal with misconduct in office.”

In practice, impeachment is the process by which a legislative body addresses charges against a government official. However, the specific definition varies from country to country: in some places – for example in Latin America – a president is only considered to have been impeached once he or she has been removed from office. In the US, however, impeachment refers to the indictment itself, no matter what the ultimate outcome of the charges; it is essentially a statement of charges against an official who can remain in office during the trial. A judgment that convicts the official on the articles of impeachment usually results in that person’s removal from office, but that is not necessarily part of its definition. Impeachment is a legal process in many countries around the world – including Brazil, France, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, Norway, Pakistan, Russia, South Korea and the US – but each one has its own rules and nuances in terms of its protagonists, process, timing and consequences.

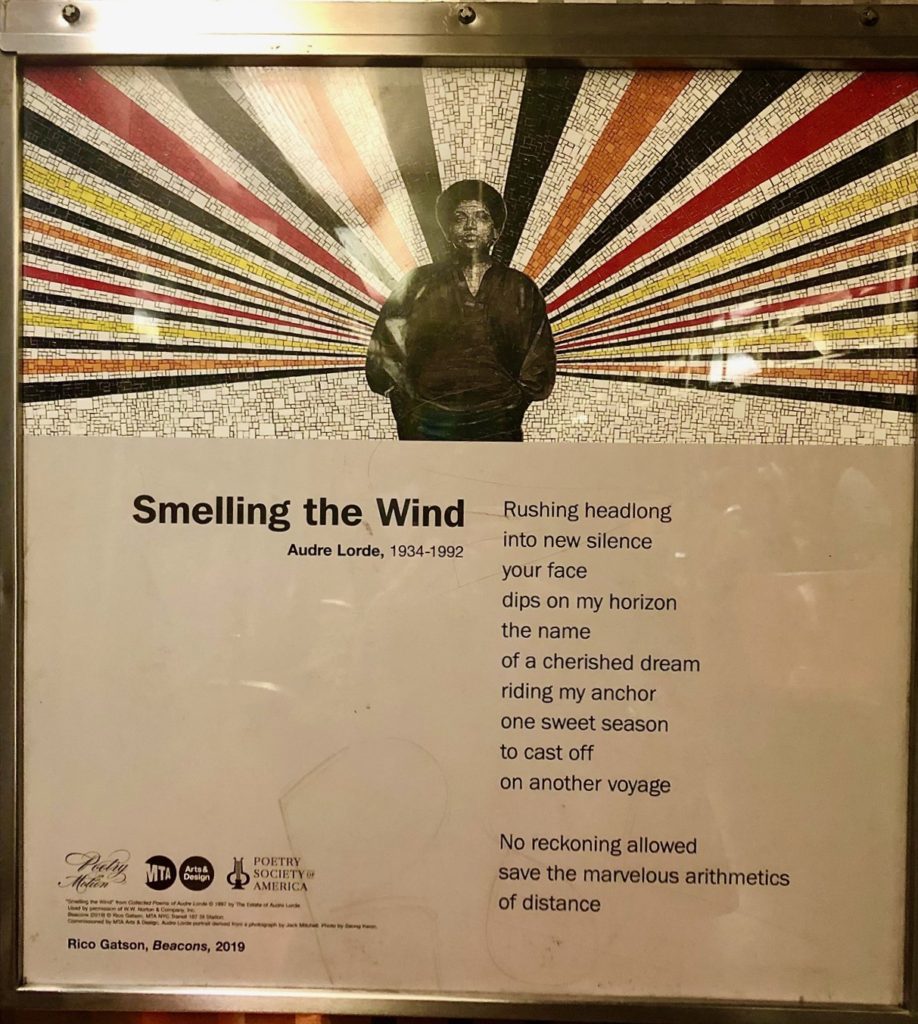

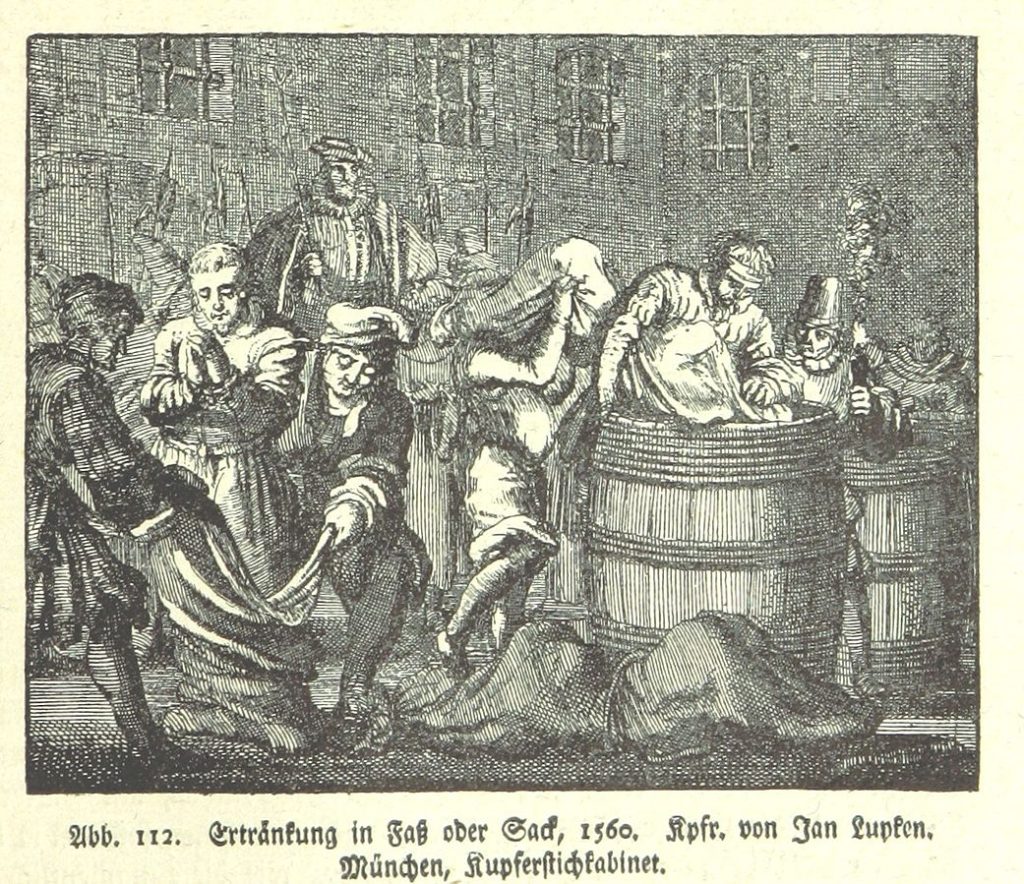

The word impeach has an equally muddy etymology, with several Latin forebears. It probably derives from the old French word empeechier, in turn from the Latin word impedīre meaning “to catch or ensnare by the foot”, and it has similarities with the modern French verb empêcher (to prevent) and the modern English impede. Back in medieval times, etymologists confused it – wrongly as it turns out – with derivations from the Latin impetere, meaning “to attack”. Some linguists argue that the word impeach is associated with the Latin impicare, which refers to a certain punishment meted out to parricides in centuries past: “punishment of the sack,” or poena cullei in Latin. This rather gruesome process involved throwing the parent-killer into the sea sewn inside a culleus, a leather sac made of cowhide covered with pitch or bitumen to slow down the process of the water breaching and filling the sac. They sometimes sewed aggressive animals – a snake, a monkey, a rooster and a dog – in with the drowning criminal to make his final hours especially torturous.

* * *

Insurrection:

“Most commonly revolt is born of material circumstances; but insurrection is always a moral phenomenon. Revolt is Masaniello, who led the Neapolitan insurgents in 1647; but insurrection is Spartacus. Insurrection is a thing of the spirit, revolt is a thing of the stomach.” – Victor Hugo

“Literature is a form of permanent insurrection. Its mission is to arouse, to disturb, to alarm, to keep men in a constant state of dissatisfaction with themselves.” –

Mario Vargas Llosa

“For those of us who have been thrown into hell, mysterious melodies and the torturing images of a vanished beauty will always bring us, in the midst of crime and folly, the echo of that harmonious insurrection which bears witness, throughout the centuries, to the greatness of humanity.” – Albert Camus

Insurrection is much more straightforward than impeachment in terms of its dictionary definition and etymology. “The action of rising in arms or open resistance against established authority or governmental restraint; with plural, an instance of this, an armed rising, a revolt; an incipient or limited rebellion.” (OED) However, as evidenced in the quotes above, it does seem historically to have had an alternative more moral, poetic, philosophical and even righteous sense that its cousins in riot, revolution and rebellion somehow lack. To my mind, it characterizes a morally justifiable reaction to oppressive and established authority almost as often as it represents a reprehensible or criminal act. (Which isn’t to say that I believe that’s true of the insurrection at the US Capitol this month.) But perhaps I’m completely wrong in any case; as H. T. Buckle stated in 1858 (see citations below): “Insurrections are generally wrong; revolutions are always right.”

Its etymology is simple: meaning “an uprising against civil authority,” it dates back to the early 15th century term insurreccion, from the Old French insurreccion or directly from late Latin insurrectionem, meaning “a rising up.”

Citations (courtesy of the OED):

Insurrection:

1459 Rolls of Parl. V. 346/2 He [Jack Cade]..wrote letters to many Citees..to have made a comon insurrection.

1461 J. Berney in Paston Lett. & Papers (2004) II. 241 Yll dysposyd persones, defame..me..how that I intend to make jnsurrexcyones contrari vnto the lawe.

1535 Bible (Coverdale) Ezra iv. 19 This cite of olde hath made insurreccion agaynst kynges.1548 Hall’s Vnion: Richard III f. xxxviij Other dyd secretely moue and sollicite the people to rise and make an insurrecion.

1587 R. Holinshed et al. Hist. Eng. (new ed.) v. xviij. 98/2 in Holinshed’s Chron. (new ed.) I The remnant of the Britains therefore withdrew..into Cornwall, and into Wales, out of which countries they oftentimes brake out, and made insurrections [1577 reyses] vpon the Saxons.

1687 A. Lovell tr. J. de Thévenot Trav. into Levant i. 277 The Moors made an Insurrection, and made one Osman their first Dey.1854 H. H. Milman Hist. Lat. Christianity II. iv. ix. 207 The people broke out in instant insurrection, declared their determination to renounce their allegiance.

1858 H. T. Buckle Hist. Civilisation Eng. (1873) II. viii. 593 Insurrections are generally wrong; revolutions are always right.

Impeach:

1569 R. Grafton Chron. II. 353 Whether the Lordes and commons might without the kings will empeche the same officers and iustices vpon their offenses in the parliament or not.1702 Clarendon’s Hist. Rebellion I. iii. 139 Mr Pym at the Bar [of the house of peers], and in the Name of all the Commons of England, impeach’d Thomas Earl of Strafford..of High Treason, and several other hainous Crimes and Misdemeanours.

1769 W. Blackstone Comm. Laws Eng. IV. xix. 261 The representatives of the people, or House of Commons, cannot properly judge; because their constituents are the parties injured; and can therefore only impeach.1863 H. Cox Inst. Eng. Govt. i. x. 229 Latimer was impeached and accused by the voice of the Commons.

1868 Trial Andrew Johnson 3 On Monday, February the 24th, 1868, the House of Representatives of the Congress of the United States resolved to impeach Andrew Johson, President of the United States, of high crimes and misdemeanors.1883 G. T. Curtis Buchanan II. xii. 247 In regard to the President, it was their duty to make a specific charge, to investigate it openly, and to impeach him before the Senate, if the evidence afforded reasonable ground to believe that the charge could be substantiated.

Impeachment:

1640–4 in J. Rushworth Hist. Coll.: Third Pt. (1692) I. 356 The Lords sat upon the Impeachment against the Judges and Bishop Wren.

1667 A. Marvell Let. 26 Oct. in Poems & Lett. (1971) II. 59 This morning seuerall members of our House did..moue the House to proceed to an impeachment against the Earle of Clarinden.

1754–62 D. Hume Hist. Eng. III. 15 (Seager) The first impeachment by the house of commons seems to have been carried up against Lord Latimer in the latter end of Edward the Third’s reign.

1789 Constit. U.S. ii. §4 The President, Vice-President, and all Civil officers of the United States, shall be removed from office on impeachment for, and conviction of, treason, bribery or other high crimes and misdemeanors.

1805 S. Chase in Life Rufus King (1897) IV. 444 Congratulations on my acquittal by the Senate of the Impeachment by the House of Representatives.

1827 H. Hallam Constit. Hist. Eng. I. ix. 566 The articles of Strafford’s impeachment.

1867 Nation (N.Y.) 14 Feb. 121 Discussion of the power of the Senate to suspend the President [Johnson] during his impeachment.